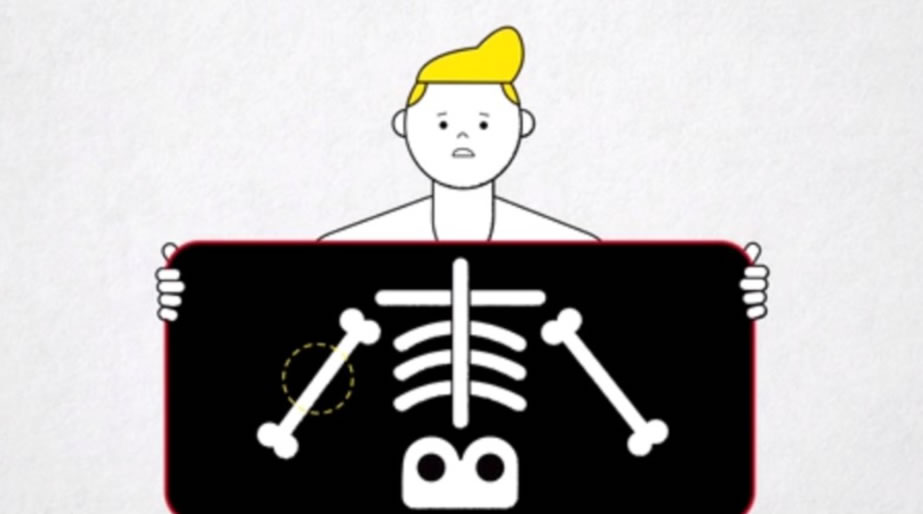

[dropcap] A[/dropcap]s many as one in two Americans has some kind of illness or condition that was, at one time, considered a pre-existing medical conditions condition by insurance companies before Obamacare.

For older Americans, that percentage is even higher: About 86% of your aging parents and grandparents, Americans between the ages of 55 and 64, have one, according to government estimates.

Before the Affordable Care Act, Americans could be denied health insurance if they had one of several of common health conditions like diabetes, asthma and even acne.

Obamacare generally stopped that practice. The law, in most cases, made it illegal for insurers to deny coverage or to charge people more because they’d been sick. It also put an end to most of the lifetime and annual benefit payment caps carried by some insurance policies, even the typically more generous employer-provided ones.

The debate about repealing Obamacare is ongoing, which means it is unclear what a final replacement law would look like. The latest Graham-Cassidy bill would eliminate federal funding for the Medicaid expansion. It would remove the subsidies that lower premiums for people on Obamacare and eliminate subsidies that help with deductibles and co-pays.

Instead, states would get a lump sum annually through 2026, and the state would decide what to do with that money. Insurers would still have to cover everyone, regardless of pre-existing conditions, but insurance companies could charge people more based on their medical history. The 10 essential health benefits all plans must carry under Obamacare would also be eliminated.

The last bill to make it through the House would leave 23 million uninsured by 2026, compared with who gets coverage under the current law, according to a Congressional Budget Office analysis. Polls show that this news worries many Americans, particularly the half who have had a condition once considered pre-existing.

But who are these people who live with these pre-existing conditions? Have they failed to “lead good lives,” as Alabama Republican Rep. Mo Brooks said in May of healthy people, who he believes should pay less for coverage? Will they really be able to buy a policy as Republicans are promising, or will the costs make coverage prohibitive?

CNN analyzed the top 10 most common conditions for Americans. People with these conditions come from all walks of life, but they each must cope with the illness they have or once had.

Eric Brod may be a confident professional in the world of finance today, but when he was a freshman in high school, something made him self-conscious.

Like a lot of high school freshmen, he had acne.

“I was probably more aware of it than my peers,” Brod said. “I was definitely thinking about it.”

Acne is one of the most common chronic pre-existing conditions and is the most common skin condition in the United States. At least 50 million people have acne, according to a 2006 national study of skin disease, the latest data available.

Acne happens when a pore in your skin gets clogged. Your body is constantly shedding dead skin cells. Sometimes, it over-produces the oil needed to keep your skin from drying out, and when that happens, dead cells can stick together and clog your pores. The bacteria that naturally live on your skin can also get caught in your pores and cause your skin to get inflamed and red. When the bacteria get deep into your skin, they can create an acne cyst.

Acne can appear on your face, your back, your chest — essentially anywhere on your skin. When your hormones are out of whack with puberty, it increases your chance of having acne, but adults can get it, too.

Prior to Obamacare, insurance companies could turn down your request for a policy or charge you more if you had this condition, even if you had it under control.

In Brod’s case, his acne wasn’t too bad, but it was persistent, and he said it wasn’t being contained with the usual antibiotics or topical medications he tried throughout his high school years.

“I was self-conscious about it and would nervously pick at it if it lingered,” Brod said. Running track and cross-country kept him fit, but it did not help his skin. He’d break out if practice was held on cold or hot days, and the sweat and dust didn’t help.

He had breakouts throughout his high school years, but the summer before freshman year of college, he had a breakthrough. His father, a dermatologist, recommended a different treatment to get it under control once and for all.

“I felt really lucky because, living with my dad, he saw how it looked from day to day and had an idea about what would help,” Brod said.

Brod got a prescription for isotretinoin, better known as Accutane, which has since been pulled from the market. It was a form of vitamin A that reduced the amount of oil released in your skin and helped the skin recover quickly. For Brod, it did the trick. He didn’t have any side effects, and the help came just in time.

“When you are going to college and you don’t know anyone, you do want to look your best,” Brod said. “Acne is more than a cosmetic concern, though. I knew it could lead to permanent scarring. And while this was a relatively mild case, I didn’t want that and was glad we found something that worked.”

Kat Kinsman has what she calls a kind of “autoimmune disease of the soul.” She struggles with anxiety and “came out” about it in a first-person story on CNN in 2014. She said it “freed me in so many ways that I felt really lucky that I had an employer and a husband who supported me through this and it didn’t blow back on me.”

More than 39 million American adults struggle with anxiety. It’s the second-most common pre-existing condition in the country, according to a 2005 study.

Kinsman now works as a senior food and drinks editor at Time Inc.’s all-breakfast site Extra Crispy, and she is the author of the book “Hi, Anxiety: Life with a Bad Case of Nerves,” published in November. However, it is something Kinsman has struggled with since kindergarten, long before she had words to describe it.

In fact, when her parents first noticed something was wrong, they took her to a doctor, who tested her for such conditions as cancer and mono. It got so bad that she missed a part of her freshman year of high school.

“Your parents can love you and take care of you the best they can,” Kinsman said. “Anxiety is not necessarily something that first comes to mind when you are looking at what is wrong.”

When doctors did finally figure it out, her parents found Kinsman the counseling she needed. “At an early age of 13 or 14, I was given this gift of openness,” she said. “Talking about my anxiety saved my life.” Though medication was not for her, she said therapy helps. She sees a nutritionist. She does a lot of deep breathing. Kinsman is not cured, but she’s better at managing it.

“I have almost 45 years of practice,” she said. “People tell me I have a real good poker face.” However, when her close friends suspect something is up, they ask to see her thumbs. She admits to a bad habit of picking at them when her anxiety is triggered. “I have sometimes picked them raw,” she said.

Her anxiety can manifest itself in other physical ways. It makes her heart pound, her body tense; it can make her sick to her stomach. “My body can decide to be a real jackass,” she said. She also gets restless and cannot sleep, and then a lack of sleep exacerbates her anxiety. Not telling people about it also compounded the problem.

“You find it so exhausting to put on your normal person suit every day and go out,” Kinsman said. “You don’t want people worried about you, and you get afraid of being thought of as crazy, or you are worried you would lose your job.”

Over the years, it has clouded her judgment, and before she talked about it, it hurt some of her relationships. A few boyfriends never understood, an employer told her not to talk about it at the office, and some friends thought she was blowing them off when she really stayed home because something had triggered her anxiety.

When she finally could talk about her anxiety, life got better. She learned that she wasn’t alone. After her essay ran, friends and even strangers would tell her about the mental illness in their own lives or within their own families.

“It was an extraordinary time,” Kinsman said. “It’s like when you look out at a meadow and you see that first firefly, and then another lights up in response and then another and another, and finally the whole meadow looks like it is on fire. People started talking to me about their own struggles, and it made me feel less of a freak and opened up the possibility for conversation.”

She hopes her talking about it can help end the stigma of mental illness. “Too many people are self-medicating or even dying because they can’t talk about it,” she said. She volunteers in the community and got certified to work on a crisis line. “I am well aware that I am in an incredible place of luxury to work where I do and to be so open and supported,” she said. “I feel like I can take this hit, and my goal is to make it easier for someone who, for whatever reason, cannot get help.”

Peter Richardson, an avid biker in Spokane, Washington, said he nearly jumped into a river when the test strips used to monitor his diabetes fell out of his pocket and into the water. “I was on a 30-mile bike ride, and about 30 dropped in. It was awful,” Richardson said.

Richardson is fit, but he’s a self-employed real estate broker who buys his own insurance, and his policy has its limits. When he went to the pharmacy to get more test strips, the pharmacist said Richardson would either have to wait four days for his insurance autorenewal to kick in or need to pay the full retail price. Unable to manage his disease without test strips, he paid. It cost him $338.

“Luckily, I can afford it, but it could easily have been a whole different scenario,” Richardson said. “I’ve got a 3-year-old daughter and a wife who stays up late at night worrying about our finances. I was blown away when the pharmacy called.” Richardson couldn’t believe insurance couldn’t cover something he regularly uses to manage his care.

Richardson is one of 30.3 million people with diabetes, according to the latest numbers from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s a pre-existing condition that left people uninsured prior to Obamacare. Luckily for Richardson, he had coverage when he was diagnosed, but his insurance didn’t cover much. He had what was known as a catastrophic policy that had high deductibles and limited benefits. His first vial of insulin cost almost $500.

“When they told me that at the pharmacy, I nearly walked out without filling it,” Richardson said. But diabetics need insulin to live.

With type 1 diabetes, the pancreases doesn’t create much, if any, insulin. Your body needs insulin to balance the glucose in your bloodstream. Glucose is what your body uses for energy. If your blood sugar is too high, it can lead to blindness or kidney or nerve damage. If your blood sugar gets too low, you could faint or even slip into a coma.

Fortunately, Richardson found a medical study to volunteer for that gave him insulin for free. That held him over until he could get better insurance.

“That really scared me,” he said. His policy is generally better now, but he can afford it. Business is doing well now. That could change if there’s another downturn in the real estate market or interest rates go up. That’s why he’s watched the health care debate with trepidation.

“That’s what keeps me up at night, because you can’t control what they are going to decide, and some of what they are considering, especially for someone like me with diabetes, is scary.”

Though he wants to stay an independent business owner, he’s been tempted to take jobs that provide benefits. “If I don’t have a sale, that may be what I’m faced with if they don’t provide coverage for people like me on the marketplace. What are you going to do?” he asked.

In the meantime, he will continue to watch what he eats. He’ll keep biking to stay fit, and he’ll monitor his health with modern tools like a program called One Drop that gives him more up-to-date data about his daily health.

Richardson hopes lawmakers will listen to the diabetic community. “Talk to the kids at the diabetic camps.

Go talk to a group of people living with the condition to give you a real-life perspective,” he said. He hopes that motivates Congress to make the system better. “It has to get better.”

When Cathy Stephens completed her first triathlon, she proudly held up a sign that said “Dear asthma, I win.”

The endurance athlete who thinks nothing of a 100-mile bike ride has such bad asthma, there are days when she cannot breathe enough to speak and she can forget about walking across the college campus where she works.

People with asthma have inflamed airways. Your lungs use airways to bring oxygen into and out of your body. When someone experiences asthma symptoms, the muscles around these airways tighten and narrow, making it hard to breathe. The cells that create mucus can also overproduce it, causing the airways to tighten more.

This happens when an asthmatic encounters something that triggers an attack. It could be something they are allergic to — In Stephens’ case, it’s mold and dust — or it could be a virus. “When people are sick around me, I run screaming the other way,” she joked.

Sometimes, asthma symptoms can be mild and make a person wheeze or cough. Sometimes, attacks can kill.

Stephens is one of 25.2 million asthmatics in the United States, according 2015 numbers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Stephens said she wasn’t breathing when she was born, and doctors had to revive her. And asthma has troubled Stephens all her life. She’s the only one of her siblings to have it. “I tell them I took one for the team,” she said. Her mom also had asthma and died of related complications in August 2016.

Despite having to raise five children by herself in small-town Idaho, Stephens said, her mother was the “real hero” who would get her through her attacks. She’d put her daughter in a hot shower so the steam could open her airways. She’d pin a towel with ice around her throat. Sometimes, she’d even sit up all night with her daughter, holding her upright.

“I have vivid memories of my mom in that rocking chair, holding me up when I was too little to prop myself up, since you can’t lay down when your asthma is bad like that,” Stephens said. Doctors also put Stephens on massive doses of prednisone, which worked but packed on the pounds.

“I was always the girl with the note for PE saying I couldn’t run, but if you looked at me, I looked fine, so I would always have to fight off that stigma that I was lazy or something,” she said.

As an adult, she feels like she has a good handle on her disease. She avoids her triggers. She watches her diet and has eliminated foods that cause inflammation. She exercises, since excess pounds can exacerbate asthma symptoms.

It’s paid off. She hasn’t been hospitalized in 20 years. She still needs to see the doctor regularly to get prescriptions for her rescue inhalers, and she’s got a nebulizer to use if her symptoms are bad. “Sometimes I’ll have to bring it to work,” said Stephens, who certifies teachers and principals and helps them find jobs. “When I have to do, that I’ll just close my door, and if someone comes in when I’m on what I call my peace pipe, no one seems to mind.”

She feels fortunate to have good insurance through her work, but she didn’t always. When she was waitressing to put herself through college, those jobs didn’t always come with benefits. Even when they did, prior to Obamacare, sometimes insurance wasn’t an option.

Companies could turn her down because of her pre-existing condition, or they would make her wait a certain amount of time before they’d cover her care. That meant she’d often put off going to the doctor or getting prescriptions filled even though she’d need to.

“I muddled my way through and mostly was lucky, but there were times when a trip to the hospital was devastating to my budget,” she said. Even now, with good insurance, her $2,000 deductible prompts her to use her inhaler — an Advair bronchodilator — sparingly. She’s been OK, but it’s not ideal.

She hopes Congress doesn’t decide to “take 10 steps back to the past,” when coverage was not as affordable as it is with the current health care bill. “It was scary when I’d have to make a choice between paying for college and paying for insurance,” Stephens said. “What bothers me about the current debate is that they talk about those of us with pre-existing conditions as being the sickest, but other than that one thing, I am much healthier than most.”

She said she’d love to take a long bike ride with any legislator who says people don’t die from a lack of insurance and see whether they see can keep up.

“They need to stop beating people up for having an illness,” Stephens said. “They should instead see what we can do when we have an environment in which we can stay healthy and live up to our full potential.”

Sleep apnea

Wendy Solon always described herself as an “active sleeper.” It never woke her up, nor did she remember any of it, but her husband told her that she’d toss and turn and snore. As she got older, her snoring got louder. She felt fine but remembered vivid dreams. After her husband continued to have problems sleeping, she talked to her doctor and asked for a recommendation to see a sleep specialist.

“I went because I thought it would help me sleep calmer and I wouldn’t be bothering my husband as much,” said Solon, 47.

She went to Emory University’s sleep clinic, where doctors “basically asked me a million questions” and suggested an overnight sleep study.

When she went in, they hooked her up to a bunch of sensors on her legs and arms, and then she went to sleep.

“I woke up, and I remember thinking, ‘Well, that’s not going to be a very interesting sleep study. I think I got a very good night’s sleep,’ and I thought for sure the doctor would tell me that he didn’t find anything,” she said.

Instead, her doctor told Solon that she woke an “astronomical number of times,” she said. The doctor recommended that she get a continuous positive airway pressure machine, or CPAP machine, to help her breathe. He diagnosed her with sleep apnea.

“I had no idea I had sleep apnea,” she said. “I wouldn’t have guessed that, ever.”

More than 25 million American adults have sleep apnea, according to the Sleep Foundation. People with the condition pause when they breathe in their sleep. The pauses can last for seconds or minutes and may happen as many as 30 times an hour. People with sleep apnea don’t often breathe deeply when they sleep.

Because they stop breathing, they go in and out of deep sleep, and that can leave them feeling tired during the day. It can have serious health consequences such as high blood pressure, stroke, obesity, diabetes and heart problems. It can cause accidents at work. It’s the No. 1 cause of sleepiness during the day, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Solon feels like using a CPAP machine is a bit like needing braces: “medically necessary but not a big deal.”

She said she doesn’t feel any more rested yet, but it helps. The CPAP machine gives her a constant stream of air pressure so her throat and airways don’t constrict and she keeps breathing during sleep. Insurance, which she gets through her husband’s company, covers the machine.

“We were blessed that we have the insurance we do, but we know we are lucky,” she said. She hopes Congress will continue to help people like her with pre-existing conditions. “For me, the sleep apnea is not a big thing compared to the other health issues in my life, but treatment does matter. It’s not like these medical situations are your fault, and they should never every be treated that way.”

Depression

The health care debate drove Mike Babb to write a highly public letter about a deeply personal issue.

“For me keeping Obamacare is a matter of life or death,” the father of two wrote in his local newspaper in Pennsylvania..

To Babb, this isn’t merely rhetoric. He is one of more than 20.8 million American adults who struggle with major depressive disorder.

“I was constantly overwhelmed with suicidal thoughts,” he said. “When you have really bad depression, this is not laziness. This is not something easy to get over. You learn you have it, and it gets even worse, because you beat yourself up for having it.”

Depression is a mental health disorder in which people have a constant feeling of despondency. It can cause them to lose interest in everyday activities and make them feel bad about themselves and others. It’s an intense sadness and feeling of hopelessness that, if not treated, can lead people to suicide.

Doctors put Babb on nearly every medication available, but none seemed to work. They then suggested a treatment that sounded more radical: electroconvulsive therapy. Once a month, he would go under general anesthesia, and doctors would send small electric currents through his brain. The currents trigger a brief seizure, changing his brain chemistry. The treatment, he said, saved his life.

“This really took a cross off my back,” he said. “It was amazing to find something that worked.”

In addition to the electroconvulsive therapy, he sees a therapist weekly. He also sees an additional psychiatrist and takes three drugs. He pays about $675 a month for COBRA — employer-based insurance for people who lose or leave their jobs — plus at least $1,500 a year with various co-pays.

It’s expensive, especially since he had to quit his teaching job due to his depression, but even when he got insurance through work, it was limited.

When he started teaching chemistry 22 years ago, he noticed that his policy carried a $50,000 lifetime cap on mental health care. Quickly, he could have surpassed that and would have had to pay for his treatment out of his savings, he said.

“Obamacare changed that,” Babb said. “Parity of service means they can’t exclude you because you suffer from something that is something mental, not physical. That has been a lifesaver for me.”

He said Obamacare gave him his life back. Though he can’t work, he still feels he has something to offer his community in Fleetwood, Pennsylvania. He’s a regular volunteer, driving for the blind, and he stays active with his hometown Lions Club. He’s there for his teenage sons.

And he promises to continue speaking up to urge congress to keep Obamacare, rather than merely repeal it. As someone who is about to get coverage through Medicaid, he worries about those proposed cuts.

“I remain very concerned with what’s going on,” he said. “I know when to speak up when stuff seems rotten.

I can’t believe these politicians would take hundreds of millions out of health care for people who really need it to give tax cuts to the rich. I hope they come to their senses soon.”

In 2001, when Karen Deitemeyer was 55, she started having trouble walking up the stairs. She had been a smoker, but with the help of two visits to a psychologist who used hypnotherapy, she had kicked the habit about a decade before.

Initially, she chalked it up to aging. “I was a little overweight at the time, and while I exercise, I probably don’t exercise nearly as much as I should,” she thought, but the problem continued.

She went to see her primary care doctor, who sent her to a pulmonologist. Tests showed that it wasn’t normal aging. She had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, known as COPD. It’s an umbrella term used to describe lung diseases that block airflow and make it difficult to breathe. More than 15.7 million Americans have it, according to a clinical review from 2013. Though many with COPD smoked at one point in their lives, it can also be genetic, and it can be caused by a person’s environment.

COPD is the third leading cause of death in the United States, and yet Deitemeyer, who is a volunteer in the COPD community, regularly gets asked what it is. “It’s a relatively newer umbrella term, so when I ask them ‘did you have an older relative with chronic bronchitis or emphysema? That’s what we call COPD now,’ and then they start to recognize it,” she said.

By the time she was diagnosed with COPD, it was considered severe, she said. “It comes on gradually. It’s not like one day you are fine and the next you can’t do anything,” she said.

Despite the severity, Deitemeyer continued to work. She had a decent job with good insurance with the Oceolo County tax collector’s office. “I was determined to make it work and just brought my oxygen tanks to the office,” she said.

She went to pulmonary rehabilitation and lost weight. Both helped her breathe better. She retired when she turned 62. “Then I finally thought it was time,” but she stays active. The 55-and-older community where she lives with her husband has an activity every day, she said. “You would not believe the calendar here. There is so much going on,” she said. She also travels the country raising awareness about COPD.

Now, 16 years after her diagnosis, she uses a stationary oxygen tank when she sleeps and a portable oxygen concentrator when she exercises or travels, but “otherwise, I don’t have to drag it around with me, so I’m fortunate in that sense,” she said.

Though she is old enough to be covered my Medicare, she is 71, she knows others with COPD who are not so lucky and she follows the health care debate closely and worries for others with pre-existing conditions.

“Who exactly is exempt from that. I mean, If you think about it, essentially life is a pre-existing condition.”

Extreme obesity

Akilah Monifa Monifa had worked as the director of communications and public affairs for the San Francisco CBS affiliate for nearly 14 years but wanted to be an entrepreneur so she could make sure more voices were heard, and down the road, she hoped to employ others.

She used severance and unemployment checks to co-found Arise 2.0 in November. It’s a multimedia publication by LGBTQ people of color created to fill a gap in coverage of that community.

She’s excited about it, but this busy Oakland mother is uncertain about her future.

“As I’ve been doing this, I’ve noticed most people who create online publications keep their day job for at least a couple of years, particularly when they have families,” Monifa said. “My big concern is health insurance.”

Monifa is covered through COBRA — employer-based insurance for people who lose or leave their jobs — but she’ll have to buy her own plan soon. That’s got her watching the health care debate with concern.

“It is something I worry about, because with the reality of this new law and what it might do with pre-existing conditions, I may not be able to afford what I need to stay healthy,” she said. “And I certainly can’t afford to go without.”

Monifa has had three of the most common pre-existing conditions. She had sleep apnea and for decades had to use a CPAP machine to help her breathe as she slept. Asthma slowed her down when she walked, and both were exacerbated by her weight.

Like more than 18.5 million American adults, she struggled with extreme obesity and has been doing everything she can to fight it.

Starting around age 15, she’d gain about 10 to 15 pounds a year. “I wasn’t mindful about what I ate,” she said, and it became a problem. At her greatest weight, her 5’11” frame carried more than 400 pounds. Over the years, she tried to lose it.

“I tried everything that I could, but I would lose 75 and then gain 100, and my weight would yo-yo back and forth, and it caused serious health problems,” she said. In addition to the asthma and sleep apnea, she had borderline high blood pressure. Her knees and back hurt. “I knew my overall life expectancy was not great,” she said

In 2012, she elected to have gastric bypass surgery. She weighed 330 pounds at the time. She made several life changes, joining group therapy and signing up for two gyms, where she continues to exercise daily. She plans meals ahead, and instead of meeting friends for dinner, they go for walks.

The effort paid off. She lost more than 222 pounds and feels great. She doesn’t even need her CPAP machine any more, and her asthma doesn’t bother her. But the fight isn’t over. She’ll need regular checkups so doctors can monitor her health and nutrition intake because she physically can’t eat as much now.

She’ll also continue to see a counselor to manage the emotional side of her eating, and she’ll stay devoted to exercise.

Even with an ankle cast for a recent injury, she is signing up for races. She recently got a medal for walking the Bay to Breakers event. “I only walked 4½ miles because the ankle was bothering me, but I was determined to do it,” she said. “You don’t lose hundreds of pounds and give up.”

Atherosclerosis

Mika Leah did everything she could to have a healthy heart, but it didn’t work, which is why she’s concerned about the possibility that insurance guarantees for those with pre-existing conditions may be dropped if Obamacare is replaced.

She’s been eating a healthy diet all her life. She developed a taste for healthy fare after her mom removed sugar and salt from the family meals when Leah’s father had his first heart attack at age 32. She’d been playing soccer since she was 5. She exercises about four to five times a week and enjoyed the gym so much, she started teaching a cycling class for fun.

But when she started having trouble running, she wondered whether something was wrong. She had run a half-marathon fine, but when she started running short distances, she felt “horrible.”

“I was extremely breathless, and when I came home, I threw up,” she said.

At first, she thought she’d push through. But when her breathing didn’t get easier and she started getting headaches, she went to the doctor, who chalked it up to stress. When the doctor summed up her life — she had an intense job and two children under the age of 2 and was going through a divorce — she replied, “Well, when you put it that way, I guess I am.”

So she kept exercising, but the symptoms got worse. The doctors continued to tell her it was stress. An EKG didn’t show any problems. It wasn’t until her 33rd birthday that they realized something else was wrong.

She and a friend went on a hike that was supposed to be easy. Leah had completed it without trouble when she was nine months pregnant. But on the first mile, she had to sit down not once but twice, and she couldn’t catch her breath.

“It felt like a 200-pound man was standing on my chest,” she said. She looked at her hiking partner, who she says could stand to lose a good 80 pounds and was a pack-a-day smoker, and realized he hadn’t broken a sweat. “I knew something was really wrong with me, and I was terrified,” she said.

She went to the cardiologist who had looked at her EKG. He too thought it was stress, but she refused to accept that answer. She demanded a stress test.

A couple weeks later, doctors put her on a treadmill to run. She stepped off, and a doctor came in to tell her she needed surgery right away, she said: Her left artery was 98% blocked. The blockage was extremely close to her heart.

She’s since had three procedures and five stents put in her heart.

Heart disease is the No. 1 killer of women, and atherosclerosis, or clogged arteries, which can lead to heart problems, are one of the top 10 most common health conditions for Americans. About 16 million American adults struggle with it, according to a 2008 study.

As she recovered, Leah became reflective and decided the job that brought her true joy, her cycling class, was what she wanted to do full-time. She founded Goomi, a wellness company that brings fitness and cooking and meditation classes to workplaces and schools across the country. Goomi means rubber band in Hebrew and is meant to symbolize bouncing back and flexibility.

Leah said she is deeply concerned about insurance and tries not to get political, but as a new business owner, she watches the health care debate closely and remains concerned about the cost of care. She hopes her company and her volunteer work for the American Heart Association will help keep people healthy and especially empower patients. Though she knows it may sound cheesy, she hopes someday, it will save lives.

“Had I not spoken up, I could easily have been one of those athletes that goes for a run and drops dead because of my heart,” she said. “It makes a difference if you speak up on behalf of your health.”

Lori Dorn, a writer for Laughing Squid, an online site that covers arts, culture and technology, said she’s become a kind of “medical sherpa” over the years, trying to help friends and acquaintances navigate the medical system when they are diagnosed with cancer.

“I tell friends, if you or someone you know who has been diagnosed with cancer and need someone to talk to or to get you through that void and darkness or someone who can help you navigate the health care system, I am there for you,” Dorn said. That’s because she has been there, too.

Diagnosed with breast cancer in 2011, she meets the five-year definition of cancer-free but still goes in every three months for a checkup, and she’s still on medication.

When she was diagnosed with cancer, she had surgery, chemotherapy and radiation and got through it without too much trouble. “I’ve been told I’m a tough cookie,” she said.

She also has another condition: asthma. Her asthma symptoms were much worse when she was living in San Francisco, where there were a lot of old buildings with mold and dust, to which she is highly allergic, she says. “Thankfully, I haven’t had a serious attack in eight or nine years,” although she uses a rescue inhaler if needed but hasn’t been to the hospital in years.

Still, the medication for both are expensive. She is on her husband’s insurance, but without it, she says, the drugs would cost her about $20,000 a month.

“It’s expensive without it, or what would happen if I was unemployed, which has happened in the past? I don’t know what I would do,” she said. “I can’t go without them, but you see where people can’t afford their medication and have to go without. Politicians keep saying people can have their choice with health care reform, but when health care is too expensive, there are not great options in the market. That is not a choice.”

Dorn is particularly concerned that annual or lifetime limit caps could come back. She said her treatments could have easily put her over those limits.

Dorn also has questions for politicians and insurance companies that talk about pre-existing conditions as if they were something they brought on themselves. She has a gene that makes her predisposed to breast cancer. “A lot of people like myself with the genetic marker,”

Dorn said. “We were born with this. Does this mean I’ve always had a pre-existing condition? Does this mean that they want to punish people for being born with a proclivity toward a pre-existing condition? Legislation like this seems very cruel.”